08 May How Transportation Is Shaping the Future of American Cities

The suburb and the city are two of our most common built environments. Historically these two places have represented completely opposite ways of living — the city was seen as dense, crowded, dirty, dangerous, and detached from the natural environment, while the suburb was thought to be a place that reconnected us to nature, relinquished us from the crowded urban streets, and sheltered us from the dangers lurking around dark street corners. Our perceptions of the past even linger on today.

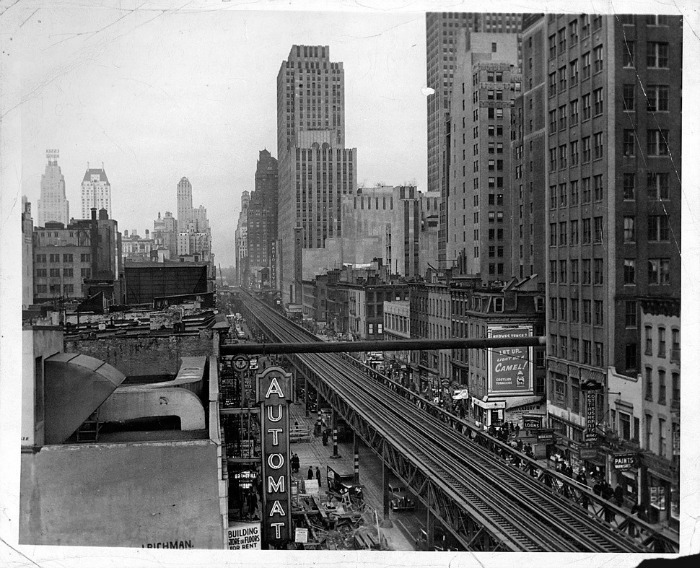

A HISTORY OF PLACE

The first suburbs were developed largely because of the electric train and streetcars which made it easy for people to live outside the city and commute in for work and leisure. But these first suburbs looked very different than the suburbs today. In Norfolk, Virginia, for example, the streetcar spurred the development of dense apartment buildings and skinny homes (Marshall, p.xi). Other suburban typologies were made up of row houses and town-homes. Although these places lacked the tall mixed-use buildings of the city, they were still built with a density that no modern suburb possesses today.

What is the reason for this? Transportation.

In the 1920’s, the dominant transportation was by foot and streetcar, and thus, the suburb remained at densities that were practical to walk to the streetcar. It wasn’t until Henry Ford made the automobile affordable for the average family that the suburb began to take the shape that it has today. After World War II, America saw an economic boom that would kick off the modern suburb that now dominates the American landscape. People began to flee the degradation of the city in exchange for the prosperities of the suburb. Our cities were soon forgotten-about places that only lower-income people could afford to live in and that had become more dangerous and dirty than ever before.

PARKING?

And so it remains until today, that the suburb is the more prolific of the two built environments. But in spite of suburban dominance, the city is becoming a place of vitality again. People are adjusting their perceptions of the city as being overcrowded, dirty, and dangerous. They are recognizing all the benefits of living in a city and many millennials are choosing, for the first time, to move into the city.

But this blog is not about whether people should live in the city or the suburb. It’s not about the benefits of living in either (we’ve already covered the economic, health and environmental benefits). This blog is about parking, and up until this point in the blog, you probably would have no idea that this was the case. You see, we can’t talk about parking without understanding the difference between these two built environments. How is each of them formed? What determines the structure of a place? The answers to these questions are determined by three things:

- politics

- economics

- transportation

For our purposes we will focus on transportation, the most powerful in shaping a place.

I began by noting that cities and suburbs have historically represented completely opposite ways of life. I say “historically” because today’s cities are becoming more and more like the suburban landscape we spent seventy-five years creating. Today many of our cities are becoming dominated by cars, wide streets, parking lots, and parking garages. People are heading to the city to fulfill something in their life that never was fulfilled in the suburb, but they are bringing their cars along with them.

City planners are requiring that both new and old buildings meet the peak parking demands so that people can have the same ease of parking that they experience in the suburbs. Residential developments have minimum parking requirements of at least one space per unit and in many cities, even more. And all of these things have drastic effects on the development of a city. So just how does transportation shape the city and the suburbs?

THE SUBURBS

Today’s suburbs have been shaped by the automobile. They sprawl out across the landscape in winding forms, emblematic of the organic curves of the natural environment. Distances between homes and stores are stretched beyond that which is practical to walk to. Sidewalks weave throughout large swaths of landscape, showcasing the fact that walking has become a form of leisure rather than a mode of transportation. Garages and parking lots sit front and center where the car glistens in all its glory. Even our social status has become represented by the car that we drive. Bike lanes, which are ironically more prevalent in the spacious roads that support the suburbs, contain only the bravest of recreational cyclists, sporting fast road bikes, spandex, and racing helmets.

Everywhere you look, the built environment reveals its reliance on the automobile. This is a simple fact. The suburbs of today would not look as they do without the automobile and it is imperative that we recognize this. You may find people in the suburbs walking or riding their bikes but this is a leisure activity, not a mode of transportation – or at least not a convenient mode of transportation.

Even rarer, you may find someone riding a bus. This is not often by choice, but instead, an indication of socioeconomic status. Public transportation is simply not a viable option in the suburbs because the distance that people must walk to a bus, light rail, or streetcar station is beyond that which is convenient. The undeniable result of the way in which suburbs were built is that the automobile will always be the dominant, most convenient, and most used form of transportation. Without higher densities, walking, biking, and public transportation cannot compete with the automobile, nor should they.

THE CITY

In the past, the city was shaped by the pedestrian and the bicycle. As technology gave us streetcars, light rails, and subways, those too defined how our city looked and behaved. These early cities — places like New York, San Francisco, Chicago, London, Paris, Barcelona, and more — are the places that millions of people travel to each year. Places like these were built before the automobile and, as a result, they are some of our most cherished and sought-out places to be, not because we despise the automobile, but because the built environment is perfectly designed for pedestrians and for interaction with people and the world around them. That fact was recognized long ago by many people including Jane Jacobs,urbanist, activist and author of The Death and Life of Great American Cities who said:

“The main purpose of downtown streets is transaction, and this function can be swamped by the torrent of machine circulation [automobiles]. The more downtown is broken up and interspersed with parking lots and garages, the duller and deader it becomes in appearance, and there is nothing more repellent than a dead downtown.” (Jacobs, p.19)

We are now in the age of the automobile and the shape of the city has changed in response. Many people want to be in the city because of all the things that great cities like the aforementioned contain, but they want that along with the convenience of the automobile. Jacobs continues by observing that,

“In a panicky effort to combat the suburbs on their own terms, something downtown cannot do, we are sacrificing the fundamental strengths of downtown – its variety and choice, its bustle, its interest, its compactness, its compelling message that this is not a way-station, but the very intricate center of things.” (Jacobs, p.19)

The cities that we love and crave to be a part of are not cities with wide roads and abundant parking. They are not places where everyone owns their own car. The cities that we travel far distances to visit are the ones that we navigate by foot, bicycle, or public transit. As people begin to move back to the city in order to be a part of the variety and choice, bustle and interest that Jacobs speaks of, they will have to face a looming reality — those types of places are not built around the automobile.

MOVING FORWARD

The movement back into the city will require people, along with governments and policy makers, to face an important decision: How much parking should we provide? Will cities continue to impose suburban parking requirements or will they recognize the importance of walking, biking, and public transit? Increased accessibility for cars will continue to reduce the demand for these other forms of transportation. This has a not-so-obvious result. The parking garages and parking lots that house our automobiles erode the fabric of the city making a city [quote]less lively, less convenient, less compact, and less safe for those who continue to have reason to use it. (Jacobs, p.353) [/quote]

Our parking requirements have a huge impact on the design of cities today. Some people despise the fact that cities like Phoenix, Los Angeles, and Atlanta are being compared to cities like New York, Chicago, or our European neighbors. They claim that comparing newer cities to the cities built before the automobile is unfair and unrealistic. I have heard them try and give Phoenix a “get out of jail free” card, as if we shouldn’t hold ourselves to the higher standards of great cities.

It is time we stop making excuses for our actions. History repeats itself, and we are not going to learn from our mistakes until we analyze our past. Our past has shown us that cheap and free parking leads to higher demand for cars, which [quote]worsens air and water quality, speeds global warming, increases energy consumption, raises the cost of housing, decreases public revenue, undermines public transportation, increases traffic congestion, damages the quality of the public realm, escalates suburban sprawl, threatens historic buildings, weakens social capital, and worsens public health, to name a few things. (Speck, p. 119)[/quote]

Marshall, Alex. How Cities Work: Suburbs, Sprawl, and the Roads Not Taken. Austin: U of Texas, 2000. Print.

Jacobs, Jane. The Death and Life of Great American Cities. N.p.: n.p., n.d. Print.

Speck, Jeff. Walkable City: How Downtown Can save America, One Step at a Time. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2012. Print.

Sara

Posted at 09:12h, 08 MayFantastic piece, and very thought provoking. I can see your argument – however, while I’ve been enjoying trekking around downtown Phoenix on my lunches recently, it has been hard at times to get friends to join me because they don’t work downtown, and have trouble with the lack of parking. I spoke with a waitress at a restaurant in Cityscape this week who’s workplace neither provides nor compensates for parking – she sometimes pays upwards of $20 a day just to be able to drive at work. Maybe you are right and this will drive (haha) the demand for more public transportation, but until then, it’s a pain. If it wasn’t a pain, though, the change would never come. Let’s hope it doesn’t take too long.

Lis

Posted at 11:23h, 08 MayThanks for the very succinct discussion! Transportation is the life blood of a city, and the form of transport without argument defines how it will live and breathe. Haussmann’s Paris project for example, during a time of horse drawn transportation and the art of walking, cut through old Paris for the purpose of redefining circulation and access. Much of the motivation behind this was for military control over uprising and dissent, the need to govern over the predominantly impoverished communities often sparking revolt and insulated by the dense labyrinth that was their home. Overall this project was seen as a success, but it resulted in the displacement of many communities. Creating a livable city for all is a delicate balance, attracting new residents, the war between integration with or displacement of existing communities, diversity, affordability, access, circulation and connectivity. In my experience while living in a more urban area with a walkable lifestyle is always desirable the prohibitive cost of modern urban living has always been an obstacle. Improved access to the city’s core with faster public transport here in Phoenix would help a great deal. My experience living in Pasadena, California and using the LA metro system was surprisingly positive. While I lived in what would be considered a suburban area outside of the LA city core, I was able to bike or walk to work, and easily access downtown LA within 20 minutes on the metro, an 11 mile distance. From my current residence to downtown PHX a 15 mile distance taking the local rail requires over an hour, which is a challenging one way time commitment. Hoping to move closer one day but until then more efficient non-car based transportation options would be wonderful! There is so much new life in downtown Phoenix and I believe far better than LA in terms of walkability downtown.